My MHST601 Journey - Final Blog

- Apr 9, 2018

- 7 min read

My MHST601 journey has shown me all roads lead from the Canada Health Act to the social determinants of health which are influenced by policy and legislation determined by the federal and provincial governments. Policy and legislation in turn have significant impact on vulnerable groups including Indigenous populations, seniors, homeless, refugees and those suffering from chronic disease to name a few based on communities, organizations and individual behaviors.

The federal government is responsible to set and administer national principles for the Canadian healthcare system aligned with the criteria of the Canada Health Act, providing financial support to the provinces and territories and funding or delivery of primary and supplementary services to certain groups of people including Indigenous populations on reserves and Inuit; whereas the provinces and territories are mostly responsible for the management, organization and delivery of health care and other social services (Government of Canada, 2016). As currently designed the Canadian healthcare system is complex, diffuse and decentralized among providers, systems and services so although we consider the Canadian healthcare system a single entity of public Medicare in fact it is fourteen single-payers, universal and public systems consisting of ten provinces, three northern territories and the federal government (CFHI, 2014). It has been identified through our studies this system of complicated policy and jurisdiction has created gaps and ambiguities in receiving equitable healthcare access for vulnerable populations and those facing chronic disease treatment and management in Canada (NCCAH, 2013).

The provinces and territories health care insurance plans must comply with the standards set out in the Canada Health Act including, public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability and accessibility in order to receive full payment under the Canada Health Transfer (Government of Canada, 2016). However the Canada Health Act does not identify how care or services should be organized and delivered or what is deemed ‘medically necessary’. This lack of a systematic approach leads to unevenness across the provinces and territories impacting overall health outcomes particularly in vulnerable populations (CFHI, 2014). This was noted when examining Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) with regards to home care, prescription drugs and rehabilitation affordability as in Ontario these are only partially funded services. While working with partners from different provinces with regards to chronic disease and vulnerable populations it was noted many initiatives have been underway to improve health outcomes through Regional Health Authorities, Public Health, Ministry of Health and Local Health Integration Networks but even more apparent was the lack of a “national” health care plan for Canadians (CFHI, 2014). Muzyka, Hodgson & Prada state “if we had a pan-Canadian health care system, we would be taking full advantage of the benefits that can be captured when we share knowledge, best practices and purchasing power for key inputs across and within jurisdictions” (2012). CFHI reported that “on overall quality of care Canada ranks as the poorest performer of 11 commonwealth countries; as it relates to access and timeliness of care; and third to last as it relates to effectiveness, safety, coordination and patient-centeredness”(2015).

Currently the Canada Health Act is the foundation of our Medicare system with its aim to ensure that all eligible residents of Canada have access to insured health services without incurring direct charges at the point of service delivery (CFHI, 2014). The Act states that “the primary objective of Canadian health care policy is to protect, promote and restore the physical and mental well-being of residents of Canada and to facilitate reasonable access to health services without financial or other barriers” (CFHI, 2014). Based on this the Canada Health Act in its purest form has served Canadians well; however it was to compliment a health care system that was conceptualized in the 1960’s and health care has and is changing significantly since its inception creating much debate regarding its viability in the 21st century (Flood & Thomas, 2016). Muzyka et al identified “we are fighting to deliver modern healthcare within the constraints of multiple outdated systems: physical infrastructure, service delivery models, provider incentives, labor contracts and the flow of information” (2012). In my practice related to COPD this is the reality we face and although tides are changing with programs such as INSPIRE we continue to manage COPD in a high cost environment and focus on acute episodic care. In Ontario it is estimated that COPD accounts for twenty-four percent of all hospital admissions in the province with a conservative estimated cost of 646 million to 736 million a year in hospital based care (CFHI, 2015). More concerning is that COPD has the highest 30 day readmission rate than any other disease in Canada at 18.8% (CFHI, 2015). This quality indicator although directed at the health care system may identify determinants existing outside the healthcare sector such as social and economic factors (CFHI, 2015).

While the Canadian Medicare system is well regarded by most Canadians there remain large disparities in healthcare related to the social determinants of health or the conditions under which people are born, grow, live work and play (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008). This was very obvious when I looked at SDOH and the relationship to chronic disease specifically COPD in my practice. The World Health Organization states that “poverty is the single largest determinant of health” (WHO, 2008). In Canada rates of hospital admissions for a primary diagnosis of COPD were three times higher for individuals with low socioeconomic status (CFHI, 2015). Pleasants, Riley & Mannino state “a disproportionate burden of COPD occurs in people of low socioeconomic status due to differences in health behaviors, sociopolitical factors and social and structural environmental exposures” (2016).

Given this information in order to improve health outcomes for people suffering from COPD health inequalities and inequities need to be addressed. Bharmel, Pitkin-Derose, Felician & Weden identify the need to adopt better governance for health and development, promote participation in policy making and implementation, further orientation to the health sector towards reducing health inequities, strengthening global governance and collaboration and monitoring progress and increasing accountability as necessities to address the SDOH (2015). Hence, there has been much emphasis placed on improving policy and legislation as the body of research grows on understanding and addressing the fundamental causes, or upstream factors of poor health and inequities related to the SDOH (Bharmel et al, 2015). It is recognized providing health care is no longer enough nor the priority in addressing the burden of illness that we are experiencing (CNA, 2013). The main action will be the focus on SDOH, health equality and equity by addressing adequate income and housing, food security, social inclusion and accessibility (CNA, 2013).

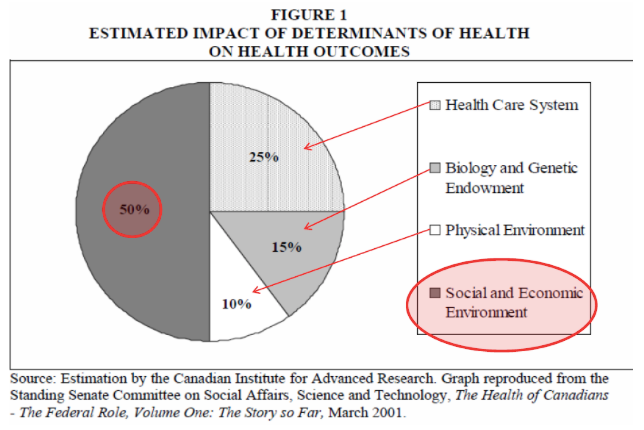

The diagram below obtained from Public Health Ontario, 2013 demonstrates the estimated impact of determinants of health on health outcomes.

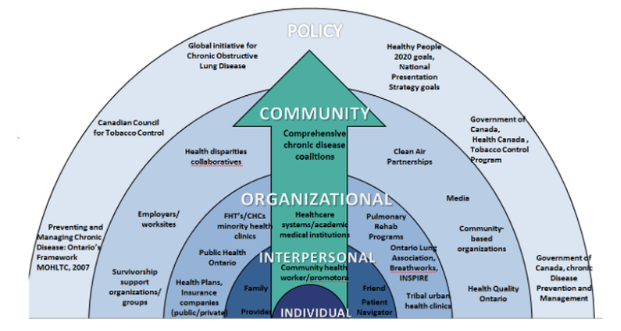

Thus knowing the impact of the social, economic and environmental factors for people suffering from COPD the Social Ecological Model (SEM) of health demonstrates how the interaction between the individual, interpersonal, organizational, community and policy spheres influence health outcomes. These five elements blend health policy and promotion, surveillance, coordination, community mobilization and engagement, self-management and care strategies to address and improve health in Canada (Davy, Bleasel,Liu, Tchan, Ponniah & Brown, 2015). None of these elements in isolation can drive health outcomes therefore support structures and management strategies must include policy and legislation, partnerships, community supports and health care system delivery and design to an individual level (National Lung Health Framework, 2012).

The SEM related to COPD:

Depicted in the above image is how Canada and Ontario are developing policies to address the macro factors that are the social structural influences on health and the health systems, clinical programs and organizations impacting COPD (WHO, 2017). Policy such as Canada’s Clean Air Act (2006), Smoke Free Ontario Modernization(2017), MOHLTC Preventing and Managing Chronic Disease: Ontario’s Framework (2007), MOHLTC Excellent Care for All Act, Patient’s First- Action Plan for Healthcare, Health Quality Ontario’s Health Equity Plan and Ontario’s Poverty Reduction Strategy 2014-2019. Policy is driven through communities and organizations to ultimately impact individual behaviors by affecting social and cultural norms (CDC, 2011). Essentially a multidisciplinary effort targeting policy, organizations and communities is required to address current health issues and future health issues such as aging, the burden of chronic disease, Aboriginal health, technology and human resources if we are to remain a viable public Medicare system (The Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology, 2002).

Canada and Canadians healthcare needs have changed but our healthcare system has not adapted accordingly. The Canada Health Act in its current state does not meet the changing needs of Canadians with regards to an aging population, Aboriginal health care needs, human healthcare resources, informed customers, technological changes and increasing rates of chronic disease (CFHI, 2014). Canada devotes vast amounts of financial and human capital to delivering healthcare services to the population but decades of research has shown that our health is primarily influenced by factors that lie outside the realm of traditional healthcare (CFHI, 2014). The future of health care will undoubtedly include further genetic research and advanced technology such as artificial intelligence; however system redesign will be required in order to invest dollars into improving the economic and social factors affecting population health versus continuing to invest in an antiquated model where providers made the rules and controlled the decisions. As demonstrated in the SEM model healthcare requires an interconnected relationship between policy, community and organizations with the individual at the heart where change will truly occur.

References:

Bharmel, N., Derose, K.P., Felician, M., Weden, M.M. (2015). Understanding the Upstream Social Determinants of Health. Rand Health. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/working_papers/WR1000/WR1096/RAND_WR1096.pd

Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (2014). Healthcare Priorities in Canada: A Backgrounder. Retrieved from http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/documents/harkness-healthcare-priorities-canada-backgrounder-e.pdf

Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (2015). COPD in Western Canada: Health, Care and Costs. Retrieved from http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/newsevents/inspired-roundtable-resources/western-copd-fact-sheet.pdf

Canadian Nurses Association (2013). Position Statement: Social Determinants of Health. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/files/en/ps124_social_determinants_of_health_e.pdf

Carey, G. & Crammond, B. (2015). Systems Change for the Social Determinants of Health. BMC Public Health. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4501117

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Strategic Framework for COPD Prevention (2011). Atlanta, GA. Available at www.cdc.gov/copd

CSDH (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, World Health Organization.

Davy, C., Bleasel, J., Liu, H., Tchan, M., Ponniah, S., & Brown, A. (2015). Effectiveness of chronic care models: opportunities for improving healthcare practice and health outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. Doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0854-8

Flood, C. M.& Thomas, B.P. (2016). Modernizing the Canada Health Act. Ottawa Faculty of Law Working Paper No. 2017-08. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2907029

Government of Canada (2016). Canada’s health care system. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-health-care-system.html

Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (2007). Preventing and Managing Chronic Disease: Ontario’s Framework. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/cdpm/pdf/framework_full.pdf

Muzyka, D., Hodgson, G., & Prada, G. (2012). The Inconvenient Truths About Canadian Health Care. The Conference Board of Canada. Retrieved from http://www.conferenceboard.ca/CASHC/research/2012/inconvenient_truths.aspx

National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.(2013). Health Inequalities and Social Determinants of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health. Retrieved from https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/determinants/RPT-HealthInequalities-Reading-Wien-EN.pdf

National Lung Health Framework (2012). Retrieved from http://www.lunghealthframework.ca/sites/default/files/LungHealthFramework_Highlights2012_EN.pdf

Pleasants, R. A., Riley, I. L. & Mannino, D. M. (2016). Defining and targeting health disparities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Vol (11): 2475-2496 doi: 10.2147/COPD.S79077

The Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology (2002). The Health of Canadians- The Federal Role. volume Two: Current Trends and Future Challenges. Retrieved from

WHO (2017). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Media Center. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs315/en/

Comments