Take a Breath: Multilevel Model of Health for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Christine Wikinson

- Mar 12, 2018

- 6 min read

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a debilitating, progressive life threatening lung disease that causes breathlessness and leads to exacerbations and serious illness (WHO, 2017). Despite the increased awareness of the risk to developing respiratory illnesses due to tobacco utilization, occupational exposures and air pollution COPD continues to carry a high burden of disease (WHO, 2017). The CDC reports approximately 75% of COPD cases are attributed to cigarette smoking, 15% to occupational related exposures and a smaller proportion from genetics, asthma, respiratory infections and indoor and outdoor pollutants (CDC, 2011). A disproportionate level of disease occurs in lower socioeconomic status due to differences in health behaviors, sociopolitical factors and social and structural environmental exposures (Pleasants, Riley & Mannino, 2016). The WHO indicates greater than 90% of COPD deaths occur in low to middle income countries (WHO, 2017). A Canadian study found there was no difference in COPD mortality between low and high education presumptively due to access to universal health coverage with high utilization of acute health care by low socioeconomic people (Pleasants et al, 2016). COPD is the fourth leading cause of death in Canada and a leading cause of morbidity in Canadian adults (WHO, 2017). It is noted the level of socioeconomic resources one does or does not have access to pertaining to education, income, status and social connections helps to protect an individual’s health or lead to illness and mortality (Cockerham, Hamby & Oates, 2017).

People of lower socioeconomic status in all countries account for the majority of all COPD patients (Pleasants et al, 2016) due to health disparities. Health disparities have the greatest impact on COPD; not only the ability to access quality care and attain goods and services that promote good health but health behaviors related to lifestyle and environment (Pleasants et al, 2016). People who lack resources to improve or maintain health are at greater risk of exposure to acquire disease and a greater risk for poor outcomes (Cockerham et al, 2017).

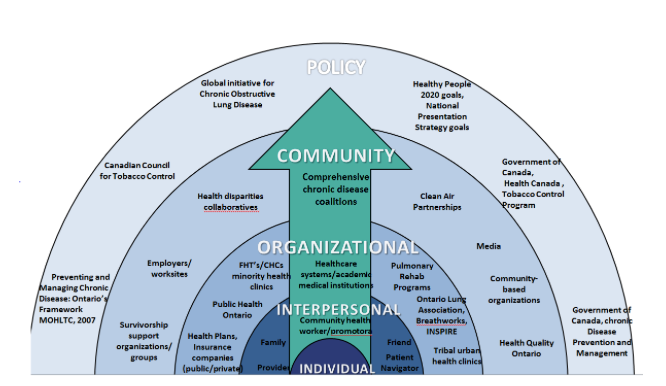

As respiratory health has a direct correlation with social, economic and environmental factors applying the Social Ecological Model (SEM) of health to COPD will demonstrate how the bands of influence between the individual, interpersonal, organizational, community and policy spheres can impact health outcomes. These five elements blend health policy and promotion, surveillance, coordination, community mobilization and engagement, self-management and care strategies to address and improve lung health in Canada (Davy, Bleasel,Liu, Tchan, Ponniah & Brown, 2015). None of these elements in isolation can drive health outcomes therefore support structures and management strategies must include policy and legislation, partnerships, community supports and health care system delivery and design to an individual level (National Lung Health Framework, 2012).

The SEM related to COPD:

The COPD National Action Plan developed in 2016 has identified five strategies that address the SEM and supports the CDC’s Public Health Strategic Framework for COPD Prevention. These include empowering people, families and caregivers living with COPD to recognize and reduce the burden of the disease, improve the prevention, diagnosis, treatment and management of the COPD by improving quality of care delivered across the continuum, collect, analyze, report and disseminate COPD related public health data that drive change and track progress, increase and sustain research and translate policy, education and program recommendations into action (NIH, 2016). Policy addresses the macro factors that are the social structural influences on health and the health systems, government policy, clinical programs and organizations (WHO, 2017). Policy that addresses tobacco utilization (age and taxes), occupational exposures, household and outdoor pollution, childhood exposures and health care access such as Canada’s Clean Air Act (2006), Canada’s Tobacco Act (1997), Smoke Free Ontario Modernization(2017), MOHLTC Preventing and Managing Chronic Disease: Ontario’s Framework (2007), CDC’s Public Health Strategic Framework for COPD Prevention (2011), MOHLTC Excellent Care for All Act, Patient’s First- Action Plan for Healthcare, Health Quality Ontario’s Health Equity Plan and Ontario’s Poverty Reduction Strategy 2014-2019 provide policy, guidelines and legislation to improve respiratory health.

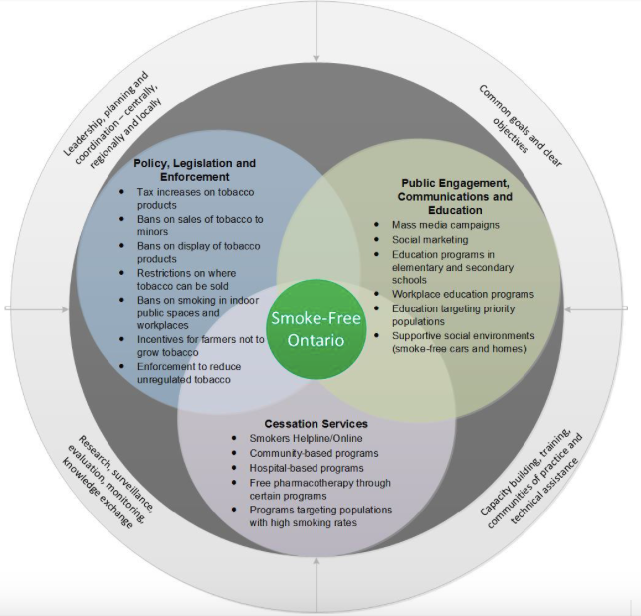

Policy whether at a federal, provincial or local level drives community and organizational initiatives through interpretation and implementation strategies. For example The Ministry of Health and Long Term Care have developed the Smoke Free Ontario Modernization (2017) plan that interconnects policy and community as demonstrated in the model below.

Smoke-Free Ontario’s Comprehensive Approach to Tobacco Control (MOHLTC, 2017)

The community facilitates individual change by leveraging resources and opportunities to collaborate with appropriate partners to develop educational resources for COPD, people with COPD risk factors, families, health professionals, provider systems, media, decisions makers and the public (CDC, 2011). Communities play a significant role in supporting education to the broader population through media campaigns, public health initiatives such as smoking cessation programs, Ontario’s Lung Association Breath Works program, supporting/adopting smoke-free policies, strong worker protection and respiratory protection programs, including surveillance and workplace air quality programs (CDC, 2011). Community agencies deliver much of the promotion/prevention in Ontario, especially that directed at populations of individuals (MOHLTC, 2007). Community strategies led by individuals, families, advocates and or agencies to improve lung health and reduce the incidence of disease is invaluable (MOHLTC, 2007).

Organizational strategies facilitate individual behavior change by influencing systems and policies (CDC, 2011). A multidisciplinary effort targeting environmental exposures, encouraging healthy lifestyles and optimizing prevention, screening, diagnosis and management requires leadership and resources from policy and community (Pleasants et al, 2016). Health care delivery is driven by policy from the federal, provincial and territories with regards to funding for programs being offered, screening and surveillance. Currently in Ontario the healthcare system is the main provider of healthcare for those suffering from COPD (MOHLTC, 2007). An organizational shift needs to occur from reactive episodic care to proactive disease management by accessing community supports including primary care and community outreach programs (MOHLTC, 2007). Programs offered by Public Health, the Breathworks Program by the Lung Association, INSPIRE and the caring for MyCOPD program are all strong community programs that provide peer support, education on COPD, nutrition, smoking cessation and medication management. It is this support that will allow people to develop self-management capabilities and change their course.

Policy, community and organizations then impact interpersonal factors. Interpersonal factors facilitate individual behavior change by affecting social and cultural norms (CDC, 2011). Community and organizations build social support networks that are invaluable for supporting patients and caregivers of COPD; the more investment there is to a community the more people benefit from a sense of belonging, shared norms and trust (Cockerham, Hamby & Oates, 2017). Social networks have the ability to support and enhance health through the promotion of healthy attitudes and policy development or consequently adversely impact outcomes if the source is an unhealthy influence (Cockerham et al, 2017). Informed and activated families and individuals impacted by COPD develop the capacity to participate fully in understanding, planning and managing their condition to stay healthy (MOHLTC, 2007).

The inner sphere is where health change will truly occur if the other bands of influence are effective. The SEM truly facilitates change to an individual level to support the individuals increasing knowledge and self-efficacy as well as positively influence attitudes and beliefs in regards to health and healthy behaviors (CDC, 2011). Key principles include information and education about the disease, training in skills to manage the disease day to day, behavior modification programs to assist with behavior changes like smoking cessation, nutritional and exercise programs, counseling and the ability to link with community partners, organizations and social resources (MOHLTC, 2007). Overall individuals are more likely to be healthy if they are supported to make healthy choices (MOHLTC, 2007).

Improving health outcomes requires fundamental system engagement, key stakeholder involvement including the individual to promote healthy behaviors (Pleasants et al, 2016) as developing and promoting healthy public policies is a shared responsibility of individuals, communities, organizations and governments (MOHLTC, 2007). The responsibility crosses many sectors including health, education, labor, social services, housing, transportation, recreation and the justice system therefore strategies and interventions are necessary to target low socioeconomic status communities by improving housing conditions, providing education on tobacco to people at a young age, reducing tobacco use and reducing other environmental factors (Pleasants et al, 2017). Each sector whether it is the individual, interpersonal, community, organization or policy has unique influences and resources that will determine the best approach to lessen the burden of COPD (Pleasants et al, 2016).

References:

Cockerham, W. C., Hamby, B. W. & Oates, G. R. (2017). The Social Determinants of Chronic Disease. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5328595/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011). Public Health Strategic Framework for COPD Prevention. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/copd

Davy, C., Bleasel, J., Liu, H., Tchan, M., Ponniah, S., Brown, A. (2015). Effectiveness of chronic care models: opportunities for improving healthcare practice and health outcomes: a systematic review. Bio med Central Health Services Research. Doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0854-8

Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (2007). Preventing and Managing Chronic Disease: Ontario’s Framework. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/cdpm/pdf/framework_full.pdf

National Lung Health Framework (2012). Retrieved from http://www.lunghealthframework.ca/sites/default/files/LungHealthFramework_Highlights2012_EN.pdf

Pleasants, R. A., Riley, I. L., & Mannino, D. M. (2016). Defining and targeting health disparities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Vol 11: 2475-2496. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S79077.

NIH (2016). COPD National Action Plan. Retrieved from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/education-and-awareness/COPD-national-action-plan

WHO (2017). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Media Center. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs315/en/

WHO (2010). A Conceptual Framework For Action On The Social Determinants of Health. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf

Comments